The headline is pretty startling: “A damning review of e-cigarettes shows vaping leads to smoking, the opposite of what supporters claim”. Well, that about wraps it up for e-cigs, then. Or, as the news report – as opposed to the academic report it purports to be about – puts it: “The review should silence lobbyists, who have long used data selectively to promote the sale of e-cigarettes.”

The headline is pretty startling: “A damning review of e-cigarettes shows vaping leads to smoking, the opposite of what supporters claim”. Well, that about wraps it up for e-cigs, then. Or, as the news report – as opposed to the academic report it purports to be about – puts it: “The review should silence lobbyists, who have long used data selectively to promote the sale of e-cigarettes.”

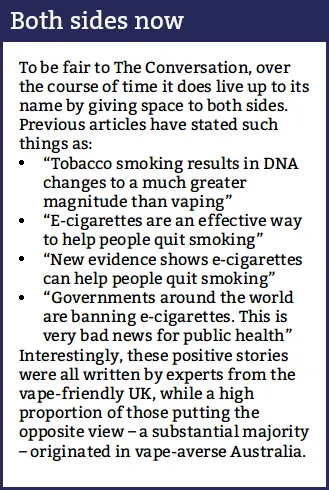

These words come from The Conversation, an online magazine backed by an impressive international list of mostly universities which claims in its masthead to provide “Academic rigour, journalistic flair” – two qualities which a cynic might think were mutually exclusive. If nothing else the authors (one of whom discloses funding from the famously anti-vaping Bloomberg Philanthropies) certainly know a thing or two about using data selectively. And with journalistic flair.

Among the nuggets they claim to have unearthed from the review “Electronic cigarettes and health outcomes: systematic review of global evidence”, published by the Australian National University, is this gem: “E-cigarette use is most common in people who also smoke.” Which is not all that different from saying use of steering-wheels is most common in people who also drive. Or maybe, given what most vapers do it for, that use of handbrakes is strongly associated with vehicle use.

In itself, the quoted statistic that roughly 53% of vapers also smoke is fairly meaningless, and certainly doesn’t support the claim that vaping leads to smoking. How much do those dual users smoke, how much have they cut down, how far are they along their journey to not smoking at all – if indeed they are on such a journey – or are they, as the Conversationalists appear to assume, going the other way? For even partial answers to those questions you would do better to consult ECigIntelligence’s consumer survey reports.

Words you won’t find in The Conversation

There can be no doubt that the authors of the academic review are no fans of vaping. Their conclusion begins: “There is strong or conclusive evidence that nicotine e-cigarettes can be harmful to health and uncertainty regarding their impacts on a range of important health and disease outcomes.”

But it will come as no surprise that their report, which runs to 360 pages, is a great deal more balanced and nuanced than the shock-horror journalistic account would suggest. Note that word “uncertainty”, which you won’t find in The Conversation’s article.

Primary among the “risks of e-cigarette use” which the review’s authors cite is poisoning, but they admit elsewhere – an admission which goes strangely unmentioned in The Conversation – that seven out of eight reported cases have been directly attributed to the illicit use of THC and/or vitamin E acetate, now known to have been the cause of the damaging, indeed deadly, EVALI outbreak in the US in 2019. The rest of their list is “toxicity from inhalation (such as seizures); addiction; trauma and burns; lung injury; and smoking uptake, particularly in youth”. Not good, admittedly, but let’s not fall into the same trap of selectivity by either ignoring these, or exaggerating them.

The review continues: “Their effects on most other clinical outcomes are unknown, including those related to cardiovascular disease, cancer, respiratory conditions other than lung injury, mental health, development in children and adolescents, reproduction, sleep, wound healing, neurological conditions other than seizures, and endocrine, olfactory, optical, allergic and haematological conditions.”

An impressive list of harms of which e-cigs have been accused, and of which this review does not completely exonerate them but which it correctly assigns to the category of “unknown”. In other words, unsupported allegations.

More words you won’t find…

The review also says: “for current smokers, there continues to be insufficient evidence that the benefits of e-cigarettes outweigh their harms.”

Note, that’s “insufficient evidence” – a phrase which occurs a total of 107 times in the paper and nowhere in The Conversation piece – not evidence to the contrary. A verdict not of “guilty”, but of “not proven”.

All in all, this doesn’t amount to a ringing endorsement of e-cigarettes; but neither does it amount to the utter condemnation that The Conversation would have its readers believe.

All in all, this doesn’t amount to a ringing endorsement of e-cigarettes; but neither does it amount to the utter condemnation that The Conversation would have its readers believe.

The journalistic flair may be lacking, but the authors of the review show more academic rigour when they sum up: “Given the extreme harms of smoking, the balance of probabilities may be that e-cigarettes are beneficial in some smokers who use them to quit smoking completely and promptly. However, since evidence on efficacy for smoking cessation is limited, multiple risks of nicotine e-cigarettes have been identified, most users continue to smoke, and their long-term effects are unknown, the ultimate balance of safety and efficacy of the use of e-cigarettes for smoking cessation is unclear.” (How much, or for how long, they continue to smoke is another thing that’s unclear – how hard and how long does a driver apply those brakes?)

Overall the review makes a strong case not for prohibition, but for regulation of e-cigarettes and their use. And that’s a case which no responsible maker, seller or user of e-cigs would disagree with. Unlike, it would seem, the black-and-white thinkers currently leading The Conversation.

– Aidan Semmens ECigIntelligence staff